In the hierarchy of WordPress® data storage, transients often occupy a misunderstood middle ground. They aren’t quite as permanent as options, yet they aren’t as ephemeral as a standard PHP variable.

The Transients API is designed to store cached data with an expiration time. It is the go-to tool for developers looking to cache expensive operations like remote API calls and complex database queries. It ensures that a single slow request doesn’t degrade the experience for every subsequent visitor.

However, beneath the simple set_transient() wrapper lies a complex relationship with the WordPress database that, if left unmanaged, can lead to significant performance bottlenecks.

Under the Hood: The wp_options Forensics

To understand how transients affect a site, we must look at how they are physically represented in the database. When a transient is created using the standard WordPress configuration, it doesn’t just create one row in the wp_options table; it creates two.

Consider the following command:

`set_transient( 'github_api_data', $value, HOUR_IN_SECONDS );`

In the wp_options table, WordPress will generate:

_transient_github_api_data: This row contains the actual serialized value of the data._transient_timeout_github_api_data: This row contains a Unix timestamp representing the moment the data should expire.

The logic follows a simple mathematical check every time get_transient is called to determine if the data is still valid:

$$\text{is\_expired} = (\text{current\_time} > \text{timeout\_timestamp})$$

If this calculation evaluates to true (meaning the clock has passed the expiration point), WordPress deletes the expired rows and returns false to the application. This false response serves as the signal to the developer that it is time to refresh the data and set the transient once again.

However, there’s a hidden danger here. It lies in how WordPress handles the autoload flag for these rows. While transients with an expiration, like our example above, are not autoloaded, any transient set without an expiration is automatically set to autoload: yes. This means every time a page is requested, those rows are pulled into memory, even if the current page doesn’t need them. If a developer inadvertently creates numerous non-expiring transients, this global overhead can quickly exceed the 1MB buffer limit of the object cache.

This means every time a page is requested, these rows are loaded into memory by the WordPress core, regardless of whether that specific page actually needs the GitHub API data. On a site with hundreds of transients, this global overhead begins to chip away at PHP memory limits.

The Garbage Collection Problem

A common misconception is that WordPress has a background process, a sort of garbage collector, that automatically deletes expired transients.

In reality, an expired transient is only deleted when it is specifically requested via get_transient(). If a plugin is deactivated, or if a developer changes the name of a transient key, the old “expired” rows may sit in the wp_options table indefinitely.

On high-traffic sites or those using dynamic naming conventions, this can result in thousands of orphaned rows. This bloat increases the size of the database index and slows down every single query targeting the wp_options table.

Manual Cleanup: Identifying and Removing Bloat

For sites with significant transient bloat, you can use the following SQL query to safely remove all expired transients from the wp_options table. This is particularly useful for cleaning up “orphaned” rows left behind by deactivated plugins or old dynamic keys.

DELETE a, b FROM wp_options a

JOIN wp_options b ON a.option_name = REPLACE(b.option_name, '_transient_timeout_', '_transient_')

WHERE b.option_name LIKE '_transient_timeout_%'

AND b.option_value < UNIX_TIMESTAMP();

This works by identifying the “timeout” row (_transient_timeout_) and checks if the stored Unix timestamp is older than the current time. It then joins the corresponding data row (_transient_). Finally, it deletes both rows simultaneously, ensuring your database stays lean and indexed properly.

Scaling with WP Engine Object Caching

One way to address the issue of transient bloat is to leverage the object cache layer provided by your hosting environment. On the WP Engine platform, object caching is a primary tool used to improve site stability, speed, and scalability.

Unlike standard WordPress installations where you might need to configure this manually, object caching is enabled by default on all new WP Engine environments. This layer acts as a specialized storage area that sits between your site and the database. When an operation like a transient request is made, the server first checks this caching layer for a result. If the data is found, it is served immediately, completely bypassing the need for a database query.

This greatly reduces the load on your server, but it’s not a bottomless storage solution. It requires a clear understanding of how your site uses transients and options, particularly those stored as autoloaded data.

The Benefits and Constraints of Object Caching

Implementing an object cache layer offers several technical advantages for high-traffic sites:

Reduced Database Latency: By storing the results of repeated queries, the server significantly reduces the time spent accessing the database.

Improved Server Health: The server stays “healthier” because it spends less energy and fewer resources searching the database for the same information repeatedly.

Intelligent Memory Management: The object cache does not clear on a fixed schedule. Instead, it uses a “Least Recently Used” (LRU) algorithm to automatically identify and remove older query results only once its allocated storage space is full.

The 1MB Buffer Caveat

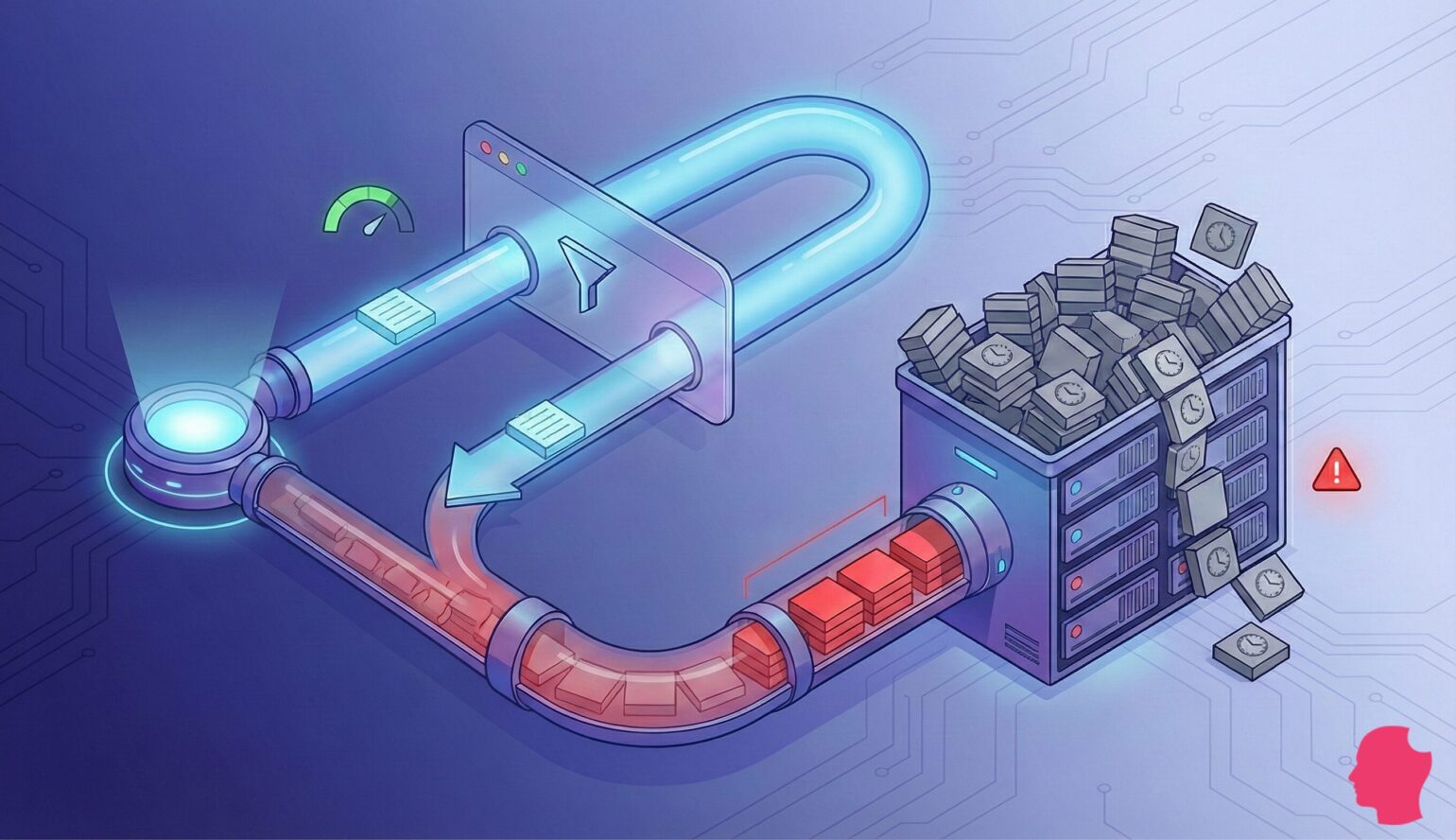

Despite these benefits, developers must be mindful of the 1MB buffer size limit. Object caching stores autoloaded values as a single long row. If your transients and other autoloaded data combined surpass what the cache can handle, the system will reject the request.

This rejection can trigger a dangerous loop. WordPress requires the data to load the page and will immediately send the request again, eventually resulting in a 502 error on the site. To maintain a healthy environment, it is recommended that all autoloaded data stays below 800,000 bytes. If you encounter persistent 502 errors after adding new transients, temporarily disabling object caching may be necessary while you identify and reduce the volume of autoloaded data.

Developer Best Practices

To maintain a healthy balance between performance and persistence, consider these updated standards for your development workflow:

Strict Namespacing: Use a consistent, unique prefix for all transient keys to make them easily identifiable during a database audit or when debugging.

The “Get/Check/Set” Pattern: Always handle the “false” return of a missing transient gracefully using the strict identity operator (=== false). Because a transient might store a “falsy” value like an empty string or the number 0, a loose check could trigger an unnecessary and expensive data refresh. Remember that a transient is a “best-effort” cache. Your code should never be written with the assumption that the data will be there when requested.

Key Length Management: Keep your transient keys under 172 characters. WordPress appends prefixes like

_transient_timeout_to your key before saving it to the database; if the total string exceeds the character limit of theoption_namecolumn, the transient may fail to save or retrieve correctly.Mind the Expiration: Avoid setting excessively long expirations for data that changes frequently. Shorter, more aggressive caching windows (e.g., 5 to 15 minutes) are often safer for maintaining site consistency and reducing the risk of serving stale content.

Conclusion

Transients are one of the most powerful tools in the WordPress developer’s arsenal, but they are not a “set it and forget it” solution. By understanding the database forensics behind the API and leveraging persistent object caching, you can ensure that your cache stays warm and your database stays lean.