Have you ever wondered what it takes to create a custom table in WordPress or why you would ever want or need to? WordPress comes with many different ways to store data out-of-the-box. Luckily for us, WordPress is flexible enough that we aren’t forced to shoehorn our every need into the ready-made solutions that come with it.

As a PHP application that depends on MySQL, we also have the option of creating our own tables in the database to meet our needs more precisely. Sometimes what might be a perfect solution for the MVP or 1.0 might not be the right choice as the software evolves.

In this article, we’ll walk through the process of creating a custom table, as well as an upgrade routine to boot.

Meet the Login Command

As a developer in the WordPress space, one of the things I really enjoy is contributing my own open-source projects. One of the most well-known of these (if you count GitHub stars) is my WP CLI Login Command project, which is a package for WP-CLI that allows you to create “magic” login links for your site. If you’re a Delicious Brains customer, you may have seen a link like this in some of the emails we send out; clicking it signs you into your account immediately — no password required. Not only is this super handy for our customers, but this kind of workflow can be a great time-saver in development as well.

I recently started rethinking some aspects of the package in preparation for breaking ground on the next major version, which led me to reconsider where and how the command stores its data in WordPress.

Going forward, we’ll use this project as an example of a codebase that could benefit from using a custom table. We won’t get too deep into the package, but use it as a practical example for context.

To CREATE TABLE or <> to CREATE TABLE?

Before we get into creating a custom table, it’s important to consider whether this is the right solution or not for your unique situation.

One way to approach this is by comparing your ideal schema (the structure your data will have in your dreamy custom tables) and the available schema’s provided by WordPress.

If you’re not particularly familiar with the landscape of the default WordPress database, you may want to take a minute to bring yourself up to speed with Iain’s Ultimate Developer’s Guide to the WordPress Database.

Take your time; we’ll wait for you 😉

Does your schema fit conceptually with the model of a Post? I.e. Does your data model have or need a title, primary content, created or modified at timestamps, or slug? If so, you may be better off using a custom post type. WordPress itself uses post types for things which you might never have thought it would, such as nav menu items and customizer snapshot changesets!

Does your data model better fit a key-value schema? WordPress has a lot of options (no pun intended) when it comes to simple key-value storage. User, post, term, and comment metadata, transients, options, and object cache APIs serve this purpose (and that’s not counting multisite).

The problem with posts, metadata and other ready-made WordPress persistence strategies is that the schema is fixed. An option only has one column to store the value. The same goes for all kinds of meta, transients and cache. In order to store a non-primitive value like an array, we’re forced to serialize it, or simply break the value into multiple keys (i.e. multiple rows in the database). Perhaps one of the primary benefits of using a custom table is that we no longer need to serialize the data. Serializing is OK for storage, but greatly reduces our ability to effectively query it. Using your own table lets you design the best schema for your needs. This gives you total freedom in querying your data and can be extremely powerful.

Creating a Custom Table

When creating a new table, it is important to get the schema right the first time as this can be a pain to change later. The schema is like the blueprint for the table. We need to define each column, as well as any attributes which may apply to it. For the Login Command, we will need the following columns:

public_key– The key used in the magic URL.private_key– The secret key for login authentication.user_id– The ID of the user that the magic login will authenticate.created_at– The date and time that the login was created.expires_at– The date and time that the login expires.

Creating a new table in the database used by WordPress is as simple as writing the SQL statement to create it, and then passing that into the dbDelta function. While not a requirement to use, the function is recommended when making changes to the database as it examines the current table structure, compares it to the desired table structure, and either adds or modifies the table as necessary.

global $wpdb;

$charset_collate = $wpdb->get_charset_collate();

$sql = "CREATE TABLE `{$wpdb->base_prefix}cli_logins` (

public_key varchar(255) NOT NULL,

private_key varchar(255) NOT NULL,

user_id bigint(20) UNSIGNED NOT NULL,

created_at datetime NOT NULL,

expires_at datetime NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (public_key)

) $charset_collate;";

require_once(ABSPATH . 'wp-admin/includes/upgrade.php');

dbDelta($sql);

Note that you should generally use $wpdb->prefix when referencing a table name in the WordPress database. This prefix is user-configurable and usually defined in your wp-config.php. We are using the base_prefix in this case as we are only creating a single table for all cli logins (like users). On multisite installs, the $wpdb->prefix will contain the blog ID in the prefix for the current site (i.e. wp_2_, wp_99_, etc.) where as base_prefix will always be the same as the main site (i.e. wp_) regardless of the current site. On single site installs base_prefix and prefix will always be the same. If your custom table will be containing site-specific data, you should use prefix to ensure the table is created for every subsite on multisite.

The dbDelta function also requires that the SQL statement you pass to it adheres to a few extra rules. These are important to review as it will cause otherwise valid SQL to fail the function’s parsing and validation.

WARNING: DO NOT LOOK DIRECTLY INTO THE FUNCTION. (source)

One problem you might run into when creating the table as I did, is an error like this:

WordPress database error Specified key was too long; max key length is 767 bytes for query

This is an error you will get when specifying the maximum length of 255 for a varchar or tinytext column. Because this is a limitation in bytes, the maximum length is different depending on the character set of the table. Gary Pendergast (a.k.a. @pento) explains in the source:

/*

* Indexes have a maximum size of 767 bytes. Historically, we haven't need to be concerned about that.

* As of 4.2, however, we moved to utf8mb4, which uses 4 bytes per character. This means that an index which

* used to have room for floor(767/3) = 255 characters, now only has room for floor(767/4) = 191 characters.

*/

$max_index_length = 191;

// wordpress/wp-admin/includes/schema.php

Now that we have the code to create our custom table, when and where do we actually run it? Enter the upgrade routine.

Creating an Upgrade Routine

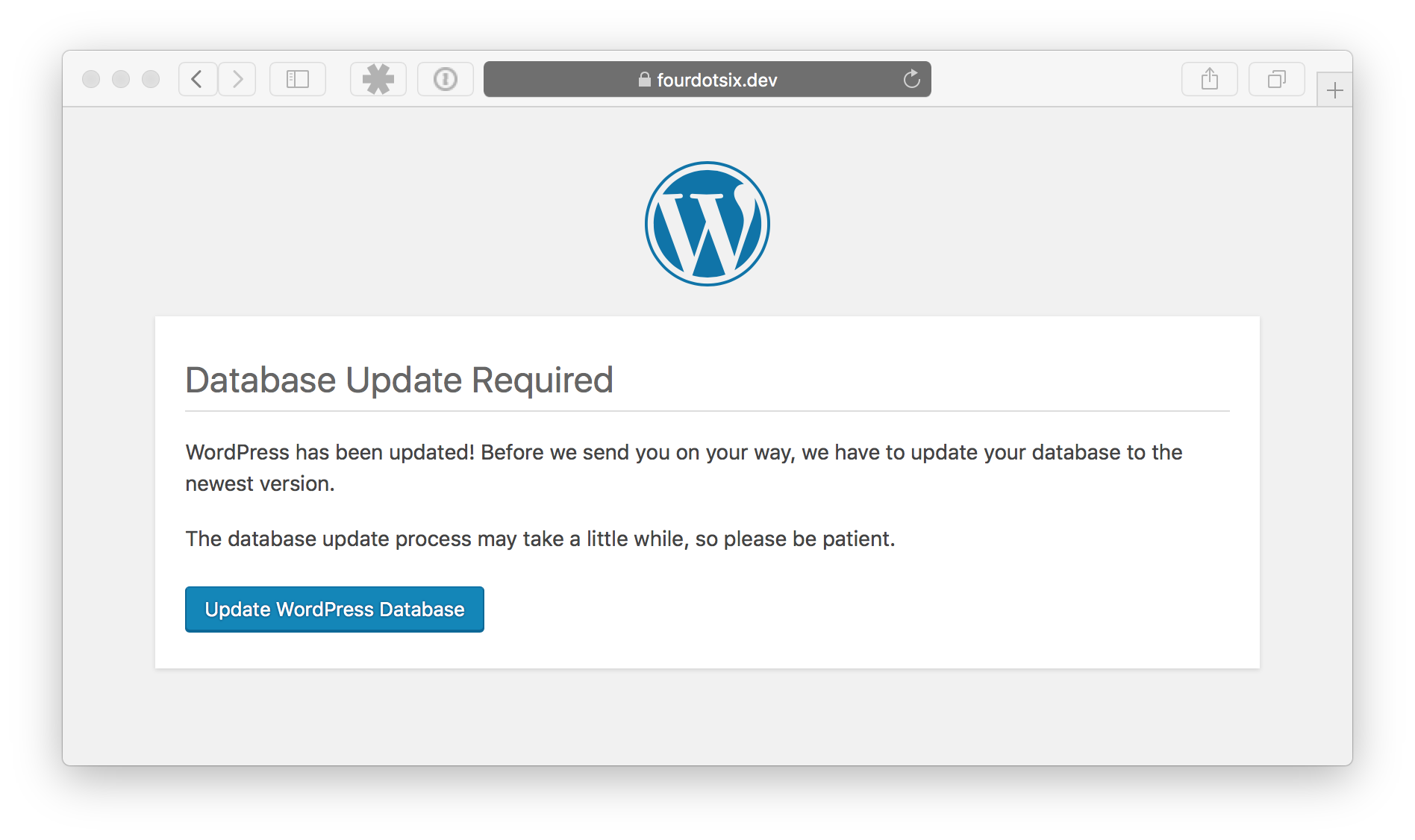

An upgrade routine is a process that is designed to update a system’s state from an older version to a newer one. You’re probably familiar with WordPress’ own screen prompting for a database update between major releases:

An upgrade routine need not be specific to performing an operation on the database, but this is perhaps the most common use-case. It consists of two basic parts: a trigger and the process(es).

The trigger is generally a simple version check which can run on load or a particular hook, often early on in a given request lifecycle. Get your current database version from the database (WordPress core stores its database version number in the db_version option; don’t change this), compare that with the version of the loaded plugin/theme, etc. If the saved version is less than the installed version, proceed with the upgrade routine and update the saved database version when it’s done. This is the most basic logic but additional checks may be necessary when controlling what routine should run next if you have multiple.

We’ll model WordPress’ version handling with our own option, and just store a simple integer for our database version.

namespace WP_CLI_Login;

function upgrade_200($wpdb) {

global $wpdb;

$charset_collate = $wpdb->get_charset_collate();

$sql = "CREATE TABLE `{$wpdb->base_prefix}cli_logins` (

public_key varchar(191) NOT NULL,

private_key varchar(191) NOT NULL,

user_id bigint(20) UNSIGNED NOT NULL,

created_at datetime NOT NULL,

expires_at datetime NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (public_key)

) $charset_collate;";

require_once(ABSPATH . 'wp-admin/includes/upgrade.php');

dbDelta($sql);

$success = empty($wpdb->last_error);

return $success;

}

function upgrade() {

$saved_version = (int) get_site_option('wp_cli_login_db_version');

if ($saved_version < 200 && upgrade_200()) {

update_site_option('wp_cli_login_db_version', 200);

}

}

In the above code, calling the \WP_CLI_Login\upgrade() function will run any upgrades that have not been applied. Currently this is just one, but gives a place to put more in the future.

Invoking the Upgrade

The importance of when the upgrade routine runs will depend largely on the upgrade and what it will do. This is especially important due to the synchronous nature of PHP; we need to be mindful of how long it will take. In this case, creating a table is a trivial amount of time so there’s not much to worry about — but when to do it? Since this will fundamentally change the way logins are stored it needs to happen before a new login can be created. The code in the command will be changed to use the new table, so if the upgrade does not run the database query to insert the record into the custom table would blow up because there is no table until the upgrade runs.

WordPress checks its internal database version on every load of wp-admin/admin.php. If the saved database version is less than the defined current version (defined in wp-includes/version.php) then you’re redirected to the above upgrade screen. Most plugins do not force the user to go through a blocking process like this to update the database, but doing so gives the user a chance to backup their database first for example. Doing things this way also requires that your new code is backwards compatible with the old way. This kind of process can also run completely in the background, without bothering the user to do anything.

In this case, the command class already has a method called ensurePluginRequirementsMet which is run before a new login is created. This currently checks that the companion server plugin is installed and that its version satisfies the version required by the command. If it does not, then the command errors out with instructions as to how to update the installed plugin (with another command!). This seems like a perfect place to check that the database is up to date and upgrade it if necessary.

A few other places this could be run are:

- On installation of the companion plugin via the login command

- On activation of the companion plugin using a plugin activation hook

Note plugin activation hooks do not get called when a plugin is upgraded - Every wp-admin request, hooked on the

admin_initaction (similar to WordPress core) - Every request, hooked on the

plugins_loadedorinitactions

Finishing Up

The final step is to update the existing code in the command which loads and saves the data that was previously stored in a transient. Since these operations have been given their own methods, there are only a handful of blocks of code that need to change.

I won’t go through every change, but here is how the code changes to save a new login to the new database instead of using a transient.

Before

private function persistMagicUrl(MagicUrl $magic, $endpoint, $expires)

{

set_transient(

self::OPTION . '/' . $magic->getKey(),

json_encode($magic->generate($endpoint)),

ceil($expires)

);

}

After

private function persistMagicUrl(MagicUrl $magic, $endpoint, $expires)

{

global $wpdb;

$data = $magic->generate($endpoint);

$wpdb->insert("{$wpdb->base_prefix}cli_logins", [

'public_key' => $magic->getKey(),

'private_key' => $data['private'],

'user_id' => $data['user'],

'created_at' => gmdate('Y-m-d H:i:s'),

'expires_at' => gmdate('Y-m-d H:i:s', $data['time'] + ceil($expires)),

]);

}

Closing Thoughts

WordPress comes with quite a few ways to persist our data. In many cases these are more than enough, and much can be done with them. If the need arises to change from one solution to another, we can write an upgrade routine to handle that.

Here are a few cases where using a custom table might be the right tool for the job:

- The data to store does not fit well conceptually to store as a post, term, user, option or metadata

- The data cannot be serialized for “queryability”

- The number of rows needed in a core table might easily reach 10’s of thousands or more

- The data will be subject to complex queries which need to be highly customized for performance

Keep in mind that the benefits come at the cost of some things we get for free with ready-made WordPress solutions like hooks and caching, in addition to the necessary work of creating and maintaining the extra table(s). Make no mistake though, when it comes to power and flexibility, nothing will be better than a well-designed schema and API built for and tuned to your specific needs.

Does your plugin or theme use a custom table? Do you have a favorite (or least favorite) plugin or theme that does? How has it worked for you? What were the pains and what were the joys? Let us know in the comments below!